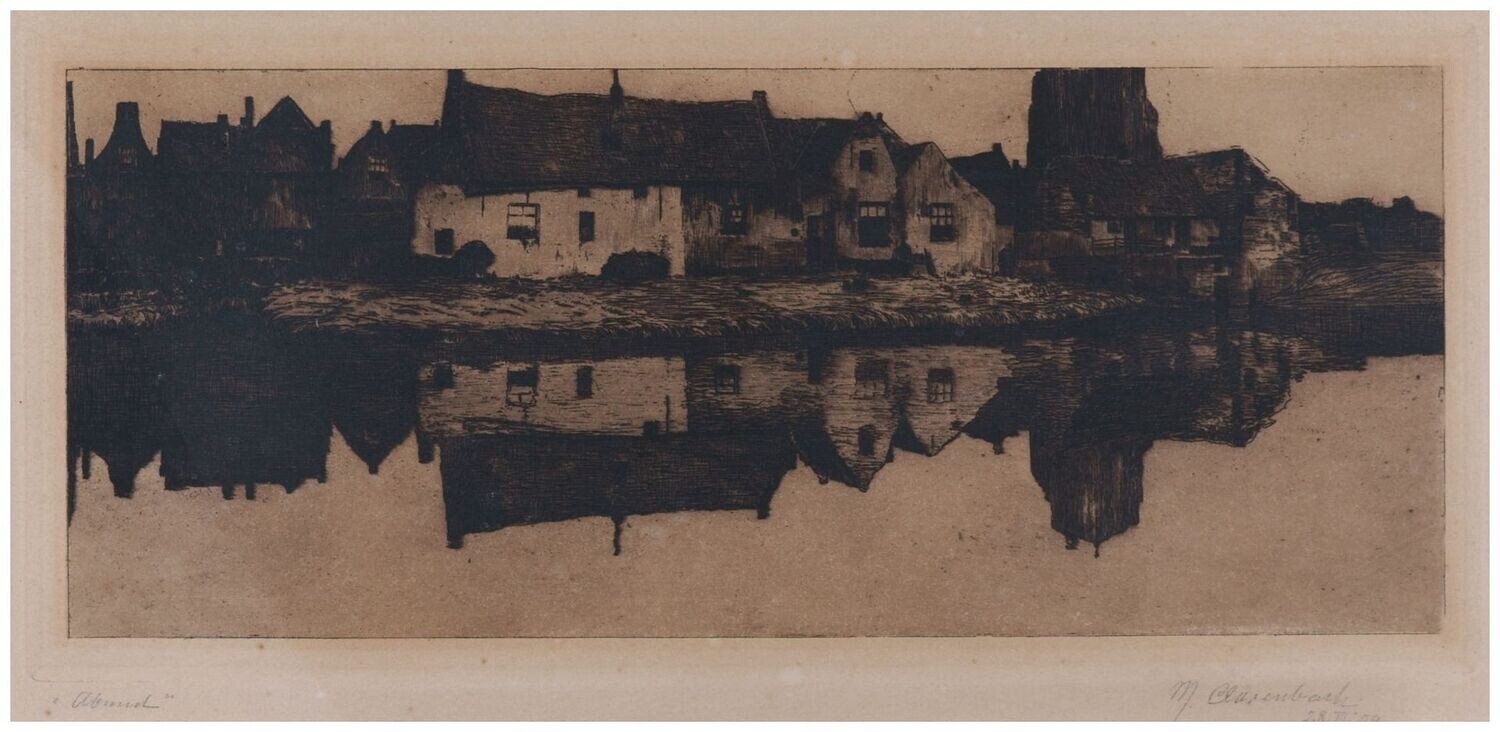

Clarenbach, Max (1880-1952), Abend, 1909

Max Clarenbach(1880 Neuss - 1952 Köln), Abend . Radierung, 18 x 41 cm (Plattenrand), 33,5 x 57 cm (Rahmen), mit Bleistift links unten als „abend“ handbezeichnet, rechts unten handsigniert und datiert „M. Clarenbach. 28.III.[19]09.“ Im Passepartout unter Glas gerahmt.

- etwas gebräunt und leicht stockfleckig, der Rahmen an den Kanten stellenweise berieben

Exposé als

PDF

- Die Tiefgründigkeit des Sichtbaren -

Die horizontal gelängte Radierung veranschaulicht panoramaartig das Antlitz einer kleinen Stadt, wie es sich von der anderen Seite des Flusses aus darbietet. Links sind giebelständige Häuser zu sehen und rechts ein mächtiger, über die Bildgrenze hinausreichender Kirchturm. Die bürgerlichen Häuser und der große Sakralbau verweisen auf den städtischen Charakter. Diese Bauten sind tonal dunkel gehalten, wodurch die hellere Häuserreihe hervorgehoben wird, die sich über die Mitte des Bildes erstreckt und näher am Wasser liegt. Der Hell-Dunkel-Kontrast etabliert zwei parallele Ebenen, die einen Imaginationsraum eröffnen, wie die Stadt wohl weiterhin beschaffen sein mag. Angespornt wird die Imagination von den beinahe gänzlich in der Dunkelheit versunkenen, kaum erkennbaren Gebäuden, während der in die Stadt hineinführende Flussarm die Vorstellungskraft zusätzlich animiert.

Da sich die Stadtsilhouette aber als Ganzes im Wasser spiegelt, werden die parallelen Ebenen als ein zusammenhängendes Häuserband wahrgenommen, das sich über die gesamte Horizontalität der Radierung erstreckt und über die Grenzen des Bildes hinaus fortzusetzen scheint. Dabei kommt der Spiegelung beinahe dieselbe Intensität wie den Häusern selbst zu, so dass sich das Gebäudeband mit ihrer Spiegelung zur dominierenden Formeinheit des Bildes zusammenschließt. Einzig parallel gesetzte Horizontalschraffuren bewirken den überzeugenden Eindruck, Wasser zu sehen, was Max Clarenbachs Meisterschaft im Umgang mit der Radiernadel vor Augen führt.

Das Wasser ist gänzlich unbewegt, das Spiegelbild nicht durch die kleinste Wellenbewegung getrübt, wodurch eine Symmetrie innerhalb der Formeinheit von Stadtlandschaft und ihrer Spiegelung erzeugt wird, die über das Motiv einer bloßen Stadtansicht hinausgeht. Es wird eine Bildordnung etabliert, die alles im Bild in sich integriert und als ein die Einzeldinge übersteigendes Ordnungsfüge einen metaphysischen Charakter aufweist. Dieser Bildordnung kommt nicht einzig in der Bildwelt eine Relevanz zu, vielmehr offenbart das Bild die Ordnung der dargestellten Realität selbst. Die metaphysische Ordnung der Realität in den Strukturen ihre Sichtbarkeit offenzulegen, treibt Clarenbach als Künstler an und motiviert ihn dazu, sich immer demselben Motivkreis zuzuwenden.

Der geschilderten Symmetrie wohnt zugleich eine Asymmetrie inne, die eine Reflexion auf die Kunst darstellt: Während die reale Stadtlandschaft von der oberen Bildkante beschnitten wird, zwei Schornsteine und insbesondere der Kirchturm sind nicht zu sehen, veranschaulicht die Spiegelung die Realität in Gänze. Und der Spiegelung kommt im Bild ein weit größerer Raum als der Realität selbst zu. Insofern die Kunst seit der Antike primär als Spiegelung der Realität aufgefasst worden ist, verdeutlicht Clarenbach hier, dass die Kunst kein bloßer Schein ist, der höchstens ein Abglanz der Realität sein kann, sondern der Kunst das Potenzial zukommt, die Realität selbst offenzulegen.

Das aufgedeckte Ordnungsfüge ist keineswegs einzig formalistischer Art, es tritt zugleich als Gestimmtheit der Landschaft in Erscheinung. Die Darstellung ist von einer beinahe sakralen Stille erfüllt. Nichts im Bild evoziert einen Laut und es herrscht gänzliche Bewegungslosigkeit. Auf Clarenbachs Landschaftsbildern sind keine Menschen zu sehen, die eine Handlung ins Bild hineintragen würden. Nicht einmal uns selbst wird ein Betrachterstandort im Bild zugwiesen, so dass auch wir nicht als Handlungssubjekte thematisch werden. Ebenso verzichtet Clarenbach auf die Darstellung technischer Errungenschaften. Das Ausblenden von Mensch und Technik erzeugt eine Atmosphäre der Zeitlosigkeit. Auch wenn die konkrete Datierung belegt, dass Clarenbach etwas veranschaulicht, dass ihm so vor Augen stand, könnten wir ohne die Datierung nicht sagen, welches Jahrzehnt oder gar welches Jahrhundert gerade herrscht. Die bewegungslose Stille führt mithin nicht dazu, dass die Zeit im Bild eingefroren wäre, vielmehr wird eine zeitlose Ewigkeit erzeugt und doch, so verdeutlicht es der eigenhändig hinzugefügte Titel „abend“, handelt es sich um ein Phänomen des Übergangs. Die Standlandschaft wird bald gänzlich in der Dunkelheit versinken, die hinteren Gebäude sind bereits nur noch schemenhaft zu erkennen. Zu dieser Übergänglichkeit passt der etwas nachgedunkelte Zustand des Blattes, welcher der Szenerie zugleich eine die Zeitlosigkeit unterstreichende Sepiaqualität verleiht. Und doch ist die Darstellung an eine ganz konkrete reale Zeit zurückgebunden. Clarenbach datiert das Bild auf den Abend des 28.3.1909, womit nicht die Anfertigung der Radierung gemeint ist, sondern das Festhalten des So-Seins der Landschaft in der Landschaft selbst.

Ist die reale Landschaft also in einem Übergang begriffen und daher etwas Ephemeres, offenbart die Kunst ihr eigentliches Sein, indem die dem Fluss der Phänomene unterworfene Realität in einen Ewigkeitsmoment überführt wird, dem ein – von der Kunst aufgezeigtes – überzeitlichen Ordnungsgefüge unterliegt. Trotz dieser Überzeitlichkeit zeigen sich auch im Bild Vorboten der Nacht als kommende Verdunklung der Welt, was der Radierung einen tief melancholischen Zug verleiht, der durch die Nachdunklung des Blattes ebenfalls befördert wird.

Aus dem philosophischen Gehalt und der lyrisch-melancholischen Wirkung des Bildes speist sich seine bannende Kraft. Haben wir uns einmal in das Bild hineinversenkt, bedarf es förmlich eines Rucks, um uns wieder von ihm zu lösen.

Die für Max Clarenbachs Kunst überaus charakteristische Radierung bildet – auch aufgrund der Ausmaße – ein Hauptwerk seines grafischen Oeuvres.

Max Clarenbach von Marie-Luise Baum /

CC BY-SA 4.0

zum Künstler

Ärmlichen Verhältnissen entstammend und früh verwaist wurde der künstlerisch hochbegabte junge Max Clarenbach von Andreas Achenbach entdeckt und bereits im Alter von 13 Jahren in die Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie aufgenommen.

„Vollständig mittellos, arbeitete ich abends bei einem Onkel in einer Kartonfabrik, um mir mein Studium zu verdienen.“

- Max Clarenbach

An der Akademie lernte er unteren anderen bei Arthur Kampf und wurde 1897 in die Klasse für Landschaftsmalerei von Eugen Dücker aufgenommen. 1902 gelang Clarenbach auf der Düsseldorfer Gewebeausstellung mit seinem Werk Der stille Tag der künstlerische Durchbruch. Das Gemälde wurde von der Düsseldorfer Galerie erworben und Clarenbach schlagartig als Künstler bekannt. Im Folgejahr, 1903, schloss er seine akademische Ausbildung ab und zog nach seiner Heirat gänzlich nach Bockum, wo er bereits seit 1901 im ehemaligen Atelier von Arthur Kampf arbeitete, der an die Berliner Akademie gewechselt war.

In Bockum widmete sich Clarenbach dem künstlerischen Studium der niederrheinischen Landschaft und entwickelte den für ihn charakteristischen Stil. Für diese Stilfindung waren auch Aufenthalte in den Niederlanden prägend. Dort studierte er die Künstler der Haager Schule und unterhielt in Vlissingen ein Atelier. Auf einer Reise nach Paris inspirierte ihn zudem die Schule von Barbizon. Derartig künstlerisch vorgeprägt widmete sich Clarenbach in der Folge ganz der Landschaft selbst, was ihn zu seiner unverwechselbaren eigenständigen Malweise führte.

„Die Natur sagt alles, man muß sie nur ruhig ausreden lassen. Jeder Baum erzählt etwas. Es ist wunderbar, aber sehr schwer, das Erzählte festzuhalten und wiederzugeben.“

- Max Clarenbach

1908 bezogen die Clarenbachs das von Joseph Maria Olbrich für den Maler entworfene Haus Clarenbach in Wittlaer, seinerzeit inmitten der Natur

„Weil Clarenbach ständig in und mit der Natur des Niederrheins leben wollte, ließ er sich hier von seinem Freunde Obricht das Haus bauen, das seinen Vorstellungen vom Schönen und Harmonischen entsprach, inmitten der Felder und der vom Schwarzbach durchzogenen Wiesen.“

- Ellen Clarenbach

Der Aufenthalt in Paris war aber auch eine Entdeckung der neuesten französischen Kunst, die im Rheinland bisher keine Anerkennung gefunden hatte. Die künstlerische Aufbruchstimmung Frankreichs auch in Düsseldorf aufleben zu lassen, führte Clarenbach mit seinen ehemaligen Akademiegefährten Julius Bretz, August Deusser, Walter Ophey, Wilhelm Schmurr und den Brüdern Alfred und Otto Sohn-Rethel 1909 zur Gründung des Sonderbundes Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler , der bis 1915 Bestand hatte. Cezanne, Monet, Renoir, Rodin, Seurat, Signac, Sisley, Vuillard, van Gogh und Picasso waren auf den Ausstellungen vertreten. Und in den Jahren 1910 und 1911 kamen Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Purrmann, Kirchner und Schmidt-Rottluff hinzu.

Die progressiven Ausstellungen des Sonderbundes wirkten auf die etablierten Kunstkreise wie ein Angriff, der nicht unerwidert bleiben sollte. Unter der Herausgeberschaft des Malers Carl Vinnen formierte sich ein "Protest deutscher Künstler" gegen die "die unpatriotische Begünstigung französischer Maler". Die Replik, in der sich auch Clarenbach zu Wort meldete, wurde unter dem Titel "Im Kampf um die Kunst" publiziert.

Nach dieser heißen Phase in Clarenbachs Lebens, nahm der weitere künstlerische Werdegang einen ruhigeren Verlauf, der es ihm erlaubte, sich abseits der politischen Wirrnisse auf seine Kunst zu konzentrieren.

Im Jahre 1917 - Clarenbach hatte bereits zahlreichen Auszeichnungen erhalten – trat er die Nachfolge Eugen Dückers als Professor der Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie an und verblieb bis 1945 in diesem Amt.

In den dunklen Jahren der NS-Herrschaft war Clarenbach auf der Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellung im Münchner Haus der Deutschen Kunst zwischen 1938 und 1943 vertreten und wurde, obwohl seine künstlerische Integrität als fraglich eingestuft worden war, 1944 in die sogenannte Gottbegnadeten-Liste unentbehrlicher Künstler aufgenommen.

Sein künstlerisches Vorgehen formulierte er mit den folgenden Worten: „Wenig Farben, wenig Pinsel. Alle Formen mutig mit dem vollen Pinsel hinsetzen, breit und flächig, nicht mit dem Pinsel Konturen zeichnen, das wäre absolut falsch. Jeder Pinselstrich hat etwas auszudrücken, nie übermalen. Dazu gehören Konzentration und große Freude an der Sache."

Letztlich ist es ein und derselbe Kreis an Landschaftsmotiven, der Clarenbach sein künstlerisches Schaffen hindurch angezogen hat.

„Das malerische Werk erweist sich - alle künstlerischen und politisch-sozialen Umbrüche der Zeit überbrückend - kontinuierlich als Ausdruck einer tief gegründeten Beziehung zur Natur und anhaltender Liebe zur niederrheinischen Landschaft.“

- Dietrich Clarenbach

Clarenbach war nicht sprunghaft, sondern, wie er es oben selbst formuliert, ‚konzentriert‘ bei seiner Kunst. Ein Oeuvre als fortwährender Vertiefungsprozess. Durch seine ausdauernde Konzentration hat er die Landschaft künstlerisch immer wieder neu erschlossen und Werke geschaffen, die den Betrachter stets von Neuem in ihren Bann schlagen.

"Nun, zum "Lauschen" gehört "Stille", und uns will scheinen, als sei das das Grundmotiv aller Clarenbach'schen Malerei.“

- Marie-Luise Baum

verwendete Literatur

Auss-Kat.: Max Clarenbach, ein Repräsentant rheinischer Kunst, Schloß Kalkum, Landkreis Düsseldorf-Mettmann, 1969.

Clarenbach, Dietrich: "Wenn man Rheinländer und dazu noch 'Nüsser' ist, kann man, was man will ..." Im Jahr 2000 jährt sich zum 120sten Mal der Geburtstag Max Clarenbachs. In: Heimat-Jahrbuch Wittlaer, Band 21 (2000), S. 53-76.

Auswahlbibliographie

Clarenbach, Max. In: Ulrich Thieme (Hrsg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Begründet von Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker. Band 7: Cioffi–Cousyns, Leipzig 1912, S. 44.

Clarenbach, Max. In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler des XX. Jahrhunderts. Band 1: A–D, Leipzig 1953, S. 446.

Vogler, Karl: Sonderbund Düsseldorf. Seine Entstehung nach Briefen von August Deusser an Max Clarenbach, Düsseldorf 1977.

Hartwich, Viola: Max Clarenbach. Ein rheinischer Landschaftsmaler, Münster 1990.

Hans Paffrath: Max Clarenbach. 1880 Neuss – Köln 1952, Düsseldorf 2001.