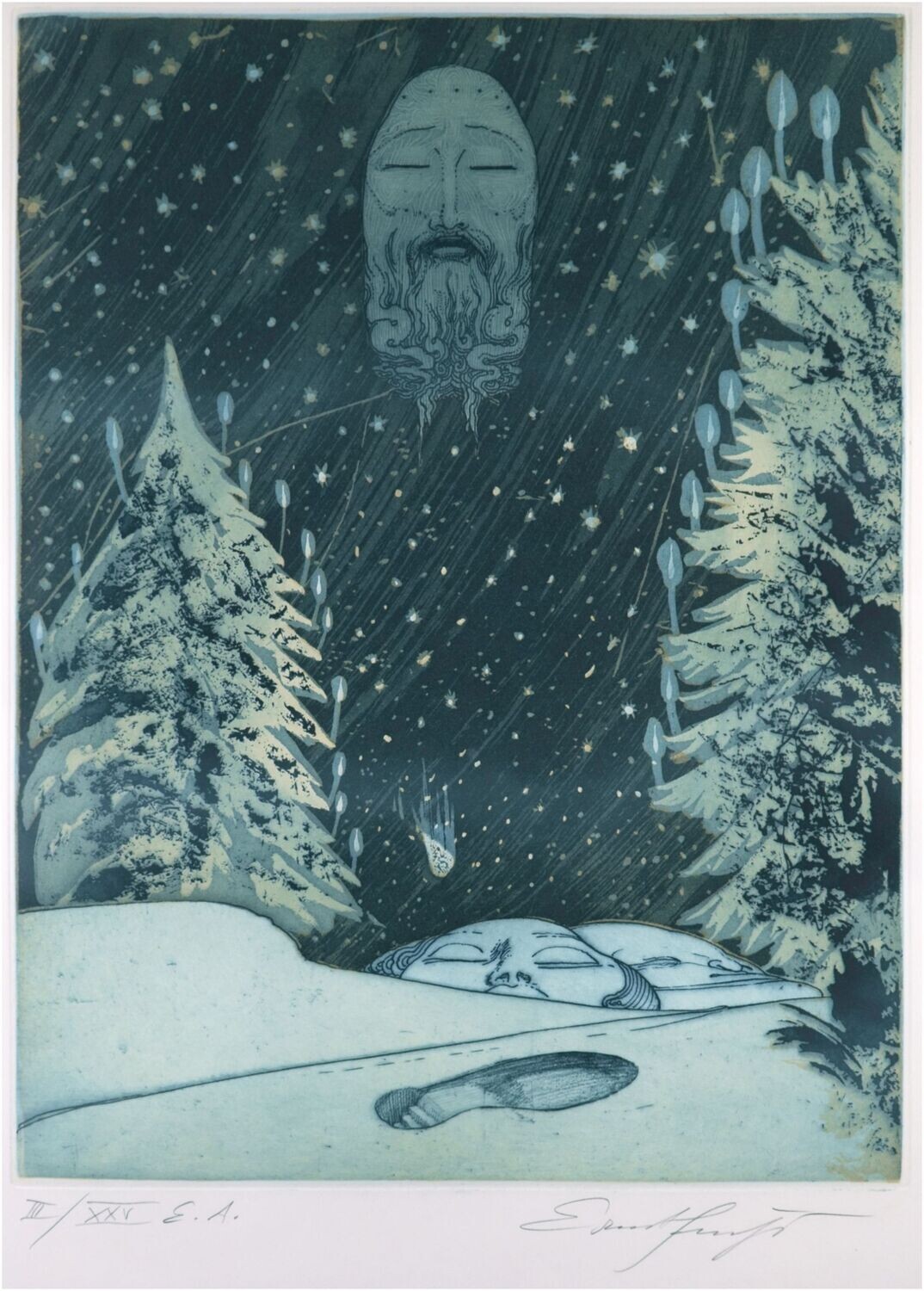

Fuchs, Ernst (1930-2015), Die verlorene Spur, 1972

Ernst Fuchs(1930 Wien - 2015 ebd.), Die verlorene Spur , 1972. Vernis mou und Aquatintaradierung, 46,8 x 36,4 cm (Plattengröße), 66 x 50 cm (Blattgröße), 69,5 x 53,5 cm (Rahmen), WVZ Hartmann Nr. 185 II d, in Blei rechts unten mit „Ernst Fuchs“ handsigniert, rechts unten mit „II/XXV“ handnummeriert und als „E.A. [Epreuvre d'Artist]“ bezeichnet. Papier mit Trockenstempel. Hinter Glas gerahmt.

- Im breiten Rand wenige minimale Knickspuren, der Rahmen mit sehr vereinzelten bestoßenen Stellen.

- Die Heilige Nacht als realer Traum -

Ernst Fuchs verwendet hier die druckgrafische Technik der im 19. Jahrhundert von Félicien Rops wiederdeckten Weichgrundätzung, die auch ‚Vernis mou‘ genannt wird. Bei diesem Verfahren wird die mit einer wachsweichen Beschichtung versehene Druckplatte mit einem Papier abgedeckt, auf welches die Zeichnung aufgetragen wird, die sich in den Untergrund eindrückt. Dies bewirkt einen weichen Strich und die Übertragung der Papierkörnung auf die Druckplatte. In Kombination mit der Aquatintaradierung erzeugt Fuchs eine äußerst malerische Wirkung mit einer intensiven Farbflächigkeit.

Wir stehen in einem nächtlichen Tannenwald aus Weihnachtsbäumen. Die brennenden Kerzen verbinden sich mit den funkelnden Sternen und den weißen Schneeflocken zu einem den Nachthimmel erfüllenden Lichtgestöber, während der Schnee seinerseits eine weißbläuliche Leuchtkraft entfaltet. Am Himmel erscheint das Antlitz Christi mit den Einstichen der Dornenkrone auf der Stirn. Mit geschlossenen Augen scheint Christus die Welt zu träumen. Auch im Schnee sind zwei Gesichter mit ebenfalls geschlossenen Augen zu sehen, die in ihrer Tiefenerstreckung die Oberfläche der Welt bilden. Auf sie stürzt wortwörtlich der Weihnachtsstern hinab. Weihnachten erscheint Gott nicht allein über der Welt, er wird in der Welt selbst präsent, was Fuchs durch den immensen Fußabdruck vor Augen führt. Er nennt das Blatt ‚Die verlorene Spur‘, doch die Spur wird im Bild nicht verwehen, sie muss allerdings aufgefunden und erkannt werden, dann zeigt sich auch, dass die Spur mehr als eine Spur ist; sie ist selbst, wie es die Stufen des Hackens veranschaulichen, der Weg. Der einzige Weg im Bild, der als motivische Umkehrung der Himmelsleiter zu Gott führt.

Mit seiner bildlichen Darstellung der Heiligen Nacht gelingt es Ernst Fuchs, das die Welt erlösende Vermittlungsgeschehen jenseits der herkömmlichen Ikonografie auf eine ebenso inspirierende wie geheimnisvolle Weise zu veranschaulichen.

zum Künstler

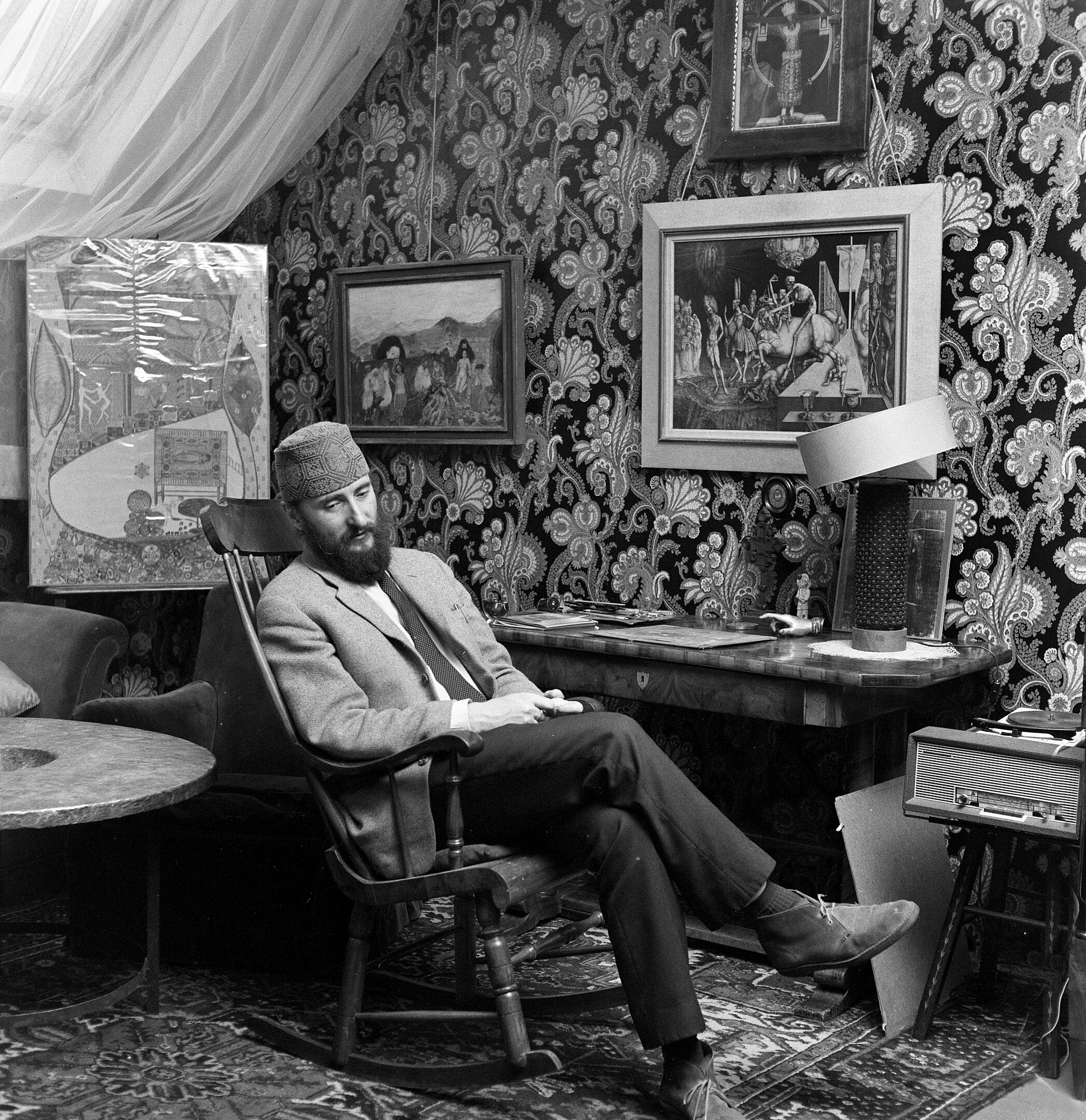

Ernst Fuchs von Gert Chesi, um 1973 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Der junge Ernst Fuchs wählt als Taufnamen ‚Ernst Peter Paul‘, eine Reverenz des gerade einmal Zwölfjährigen an Peter Paul Rubens, der ihn immer wieder inspirieren sollte. Ein erster künstlerischer Unterricht wurde ihm durch den Bruder seiner Taufpatin, Alois Schiemann, zuteil. Später besuchte er die Malschule St. Anna in Wien und 1946 wurde er in die Wiener Akademie der bildenden Künste aufgenommen, wo er unter Robin Andersen und Albert Paris Gütersloh, dem geistigen Vater der Wiener Schule des Phantastischen Realismus bis 1950 studierte. Nach zahlreichen Reisen hielt sich Fuchs länger im Dormitio-Kloster am Berg Zion in Israel auf, wo er sich intensiv mit der ihn prägenden Ikonenmalerei und der damit verbundenen spirituellen Maltechnik beschäftigte. In seinem Buch Architectura Caelestis (1966) teilt er mit, dass viele seiner Motivfindungen auf visionären Erfahrungen basieren, was er später abermals hervorhebt:

„Nicht selten gelange ich während des Malens in Trance, mein Bewusstsein schwindet zugunsten eines medialen Schwebezustandes, in dem ich mich von sicherer Hand geführt und bewegt fühle, Dinge tuend, von denen ich bewußtermaßen wenig weiß. Dieser Zustand kann mitunter mehrere Stunden dauern. Danach erscheint mir alles, was ich in diesem Zustand geschaffen habe, als ob ein anderer es getan hätte.“

- Ernst Fuchs

1962 kehrte Fuchs nach Wien zurück, wurde zum Professor an der Akademie berufen und zum wohl einflussreichsten Protagonisten der Wiener Schule des phantastischen Realismus, die 1959 im Belvedere ihre erste Gruppenausstellung präsentiert hatte. Neben Ernst Fuchs waren Arik Brauer, Rudolf Hausner, Anton Lehmden, Helmut Leherb und Güterslohs Sohn, Wolfgang Hutter, Hauptvertreter dieser Kunstströmung.

1972 erwarb Fuchs die Otto-Wagner-Villa, die er in kongenialer Weiterführung des Wiener Jugendstils zu seinem Privatmuseum gestaltete. In den 70er Jahren entwickelte sich auch die Künstlerfreundschaft mit Salvator Dalí und Arno Breker, die Dalí 1975 in die Worte fasste: „Wir sind das Goldene Dreieck der Kunst: Breker-Dalí-Fuchs. Man kann uns wenden, wie man will, wir sind immer oben.“

Fuchs bestätigte sich auch als Sänger spiritueller Lyrik und widmete sich ab den 1990er Jahren zusehends seiner phantastischen Architektur. Die in der Otto-Wagner-Villa verfolge Idee eines Gesamtkunstwerks schlug sich auch in der Gestaltung von Gebrauchsgegenständen nieder. So wurde ein BMW 635 CSi nach seinem Entwurf zum „Feuerfuchs auf Hasenjagd" und die Porzellanmanufaktur Rosenthal fertige zahlreiche Produkte nach seinen Vorlagen an.

In seiner Kunst schöpft Ernst Fuchs aus der Fülle der Tradition, aus der sein Genius eine ganz neue Semantik gebiert:

„Erkenntnisse suchen mich heim, die zu finden ich gar nicht gehofft hatte. Von dieser Geistlichkeit erfasst, begreife ich auch, was die großen Erkenntnisse anderer Maler waren, die meine Bewunderung erregten. Ein Verständnis der Kunst und der Erkenntnis, die sie vermittelt, erfasst mich, so, als ob mein Geist mit allen Künstlern aller Epochen in einen Diskurs geraten wäre.“

- Ernst Fuchs

Auswahlbibliographie

Quelltexte

Ernst Fuchs: Architectura Caelestis - Images Of The Hidden Prime Of Styles (Die Bilder des verschollenen Stils), Frankfurt a. M. 1966.

ders.: Im Zeichen der Sphinx. Schriften und Bilder. Hrsg. v. Walter Schurian, München 1978.

ders.: Aura. Ein Märchen der Sehnsucht, München 1981.

ders.: Phantastisches Leben. Erinnerungen, Berlin 2001.

Werkverzeichnis

Helmut Weis: Ernst Fuchs. Das graphische Werk. 1967 - 1980, München 1980.

Literatur

Gerhard Habarta: Ernst Fuchs. Das Einhorn zwischen den Brüsten der Sphinx. Eine Biographie, Graz 2001.

Friedrich Haider (Hrsg.): Ernst Fuchs. Zeichnungen und Graphik aus der frühen Schaffensperiode mit Hinweisen auf die Malerei 1942-1959, Wien 2003.

Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hrsg.): Phantastischer Realismus. Arik Brauer, Ernst Fuchs, Rudolf Hausner, Wolfgang Hutter, Wien 2008.