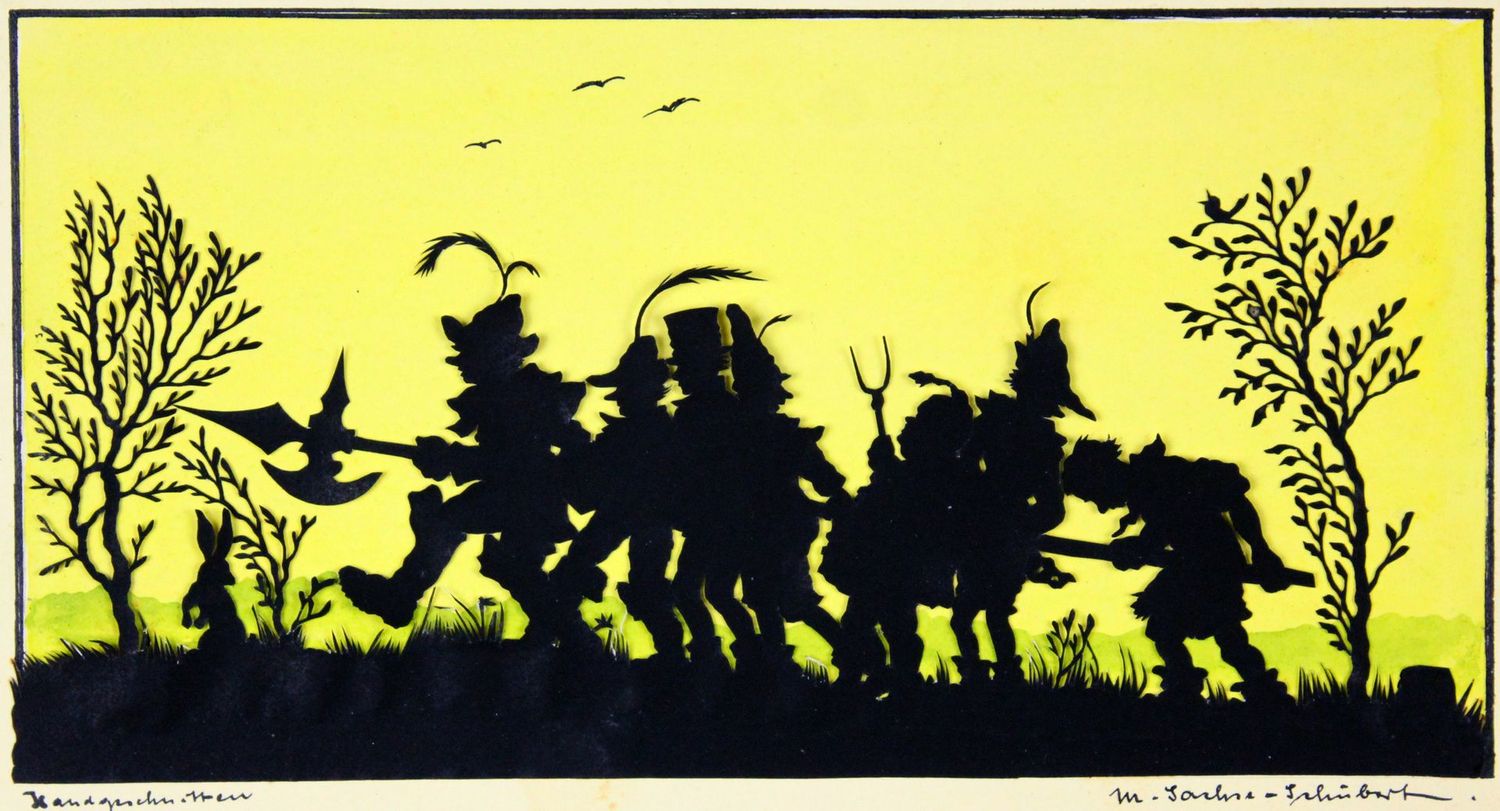

Sachse-Schubert, Martha (1890 - nach 1949), Die sieben Schwaben, um 1915

Martha Sachse-Schubert(1890 - nach 1949). Die sieben Schwaben , Scherenschnitt auf gelb getuschtem Fond, 9,2 x 17,6 cm (Bildgröße), 16 x 25 cm (Blattgröße), rechts unten signiert „M. Sachse-Schubert.“, links unten mit dem Vermerk „handgeschnitten“ versehen, um 1915.

Unter dem Scherenschnitt ist der Vers von Albert Lortzing notiert:

„I wills den Leute zeigen

Was Klugheit alles kann;

I bin kei dummer Schwoabe,

I bin a gescheiter Man.“

zum Werk

Der dem Sujet entsprechend sehr breitformatige Scherenschnitt zeigt die Sieben Schwaben wie sie dem links im Gehölz sitzenden Hasen - dem vermeintlichen Untier - entgegen ziehen. Die Sieben Schwaben sind durch die äußerst fein-filigrane Gestaltung der Körperformen und Physiognomien ihrer jeweiligen Charaktertypik entsprechend herausgearbeitet. Trotz dieser Verschiedenheit halten sich die wackeren Recken allesamt an der dicken Stange der Lanze fest, ohne die sie hinzustürzen drohten. Entsprechend verdutzt blickt der Hase auf den kuriosen Trupp, der es offensichtlich auf ihn abgesehen hat. Das Drollige der Tollpatschigkeit liegt gerade in der naiven Gemeinschaftlichkeit der Schwaben, die mit ihrer Schlachtordnung des Unbilden des Lebens zu trotzen suchen. Damit sind die Sieben Schwaben zugleich eine Allegorie auf die komödienhaften Anstrengungen des Menschen. Erhöht wird die Dramatik dieser allgemeinmenschlichen Komödie durch den eindrucksvollen Gelb-Schwarz-Kontrast der Darstellung.

zur Künstlerin

Die Silhouettenmalerin und Scherenschnittkünstlerin Martha Sachse-Schubert war die Enkelin des Bildhauers Hermann Schubert und Tochter des Silhouetteurs Edwin Schubert. Die Künstlerin war in Leipzig tätig und schuf zahlreiche Scherenschnitte. Darunter auch viele Vorlagen für Buchillustrationen.

Öffentliche Sammlungen, die Werke von Martha Sachse-Schubert besitzen:

Stadtgeschichtlichen Museum Leipzig.

Auswahlbibliographie

Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker (Hrsg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, Bd. 30, Leipzig 1935, S 297.

Heinz Rölleke (Hrsg.): Grimms Märchen und ihre Quellen. Die literarischen Vorlagen der Grimmschen Märchen synoptisch vorgestellt und kommentiert, Trier 2004.

Der im asiatischen Raum wahrscheinlich als Schablonen für Porzellanmalerei bereits im 12. Jahrhundert gebräuchliche Scherenschnitt ging in Westeuropa aus der im 18. Jahrhundert verbreiteten Kunst des Schattenrisses hervor. Benannt nach dem französischen Finanzminister Étienne de Silhouette, auf dessen sprichwörtlichem Geiz die Anekdote basiert, er habe sein Haus statt mit Ölbildern mit schwarzen Scherenschnitten ausgestattet, war die in den 30er Jahren des 18. Jahrhunderts aufkommende Bezeichnung ‚Silhouette‘ zunächst ein negativer Ausdruck für ‚billige Kunst‘. Die Silhouette knüpfte jedoch an eine Tradition an, welche ihre abwertende Bedeutung schnell überblendete. Nach der von Plinius dem Älteren überlieferten Legende ist der Schattenriss nämlich der eigentliche Ursprung der Malerei: Eine junge Korintherin hatte den Schatten des Kopfes ihres zur Seefahrt aufbrechenden Geliebten auf einer Wand nachgezeichnet. Diese Legende beinhaltet jene beiden wesentlichen Momente, die den Schattenriss in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts zu einer alle Gesellschaftsschichten durchziehende Mode hat werden lassen. Zum einen stellt der Schattenriss ein authentisches Abbild her, zum anderen ist er eine Projektionsfläche der Sehnsucht. Aus dieser Verbindung von Realismus und Imaginationspotenzial schöpft der von der Darstellung des menschlichen Profils losgelöste Scherenschnitt. Der Schatten wird zum künstlerischen Material, mit dem szenische Darstellungen geschaffen werden, die eine hohe Affinität zum Märchenhaft-Phantastischen aufweisen und dabei zugleich authentisch wirken. Daher war der Scherenschnitt nicht allein für die Aufklärung und Empfindsamkeit, sondern ebenfalls für die Romantik, den Klassizismus und das Biedermeier relevant. Diese Kunst erfreute sich bis ins zwanzigste Jahrhundert hinein großer Beliebtheit und wurde von so unterschiedlichen Künstler wie Philipp Otto Runge und Henri Matisse ausgeübt.